No doubt about it. This was a tough weekend. The Zimmerman decision took most Americans somewhere. I’d followed the trial because it encompassed so many themes of my own life, and because I am a courtroom junkie. The decision didn’t surprise me, nor did the reaction to it. What did surprise was how disenfranchised I felt–so white. I was no longer the friend, the teacher, the person who has devoted a great part of her life to making others feel worthwhile. I was, to many, merely “one of them.”

No doubt about it. This was a tough weekend. The Zimmerman decision took most Americans somewhere. I’d followed the trial because it encompassed so many themes of my own life, and because I am a courtroom junkie. The decision didn’t surprise me, nor did the reaction to it. What did surprise was how disenfranchised I felt–so white. I was no longer the friend, the teacher, the person who has devoted a great part of her life to making others feel worthwhile. I was, to many, merely “one of them.”

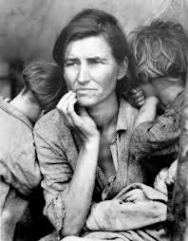

One of the terms that surfaced again and again as the trial was hashed and rehashed is “white privilege.” If you’re not aware of the descriptor, Wikipedia covers it quickly. It’s a relatively new concept that puts white people, privileged people, in the role of “oppressor.” What is dangerous to me about this is that it is, like so many other themes, created to divide rather than blend, hugely divisive. It’s also dismissive of this country’s history. The Great Depression, The Dust Bowl, and so many other periods united Americans in shared suffering and poverty. Don’t get me wrong, all things being equal, I think it’s still far more difficult to be black in America–in the world for that matter– than white, but it’s that divisive them and us that I fight every step of the way. Rush, Al, and Jesse all have become rich by having us tear into each other.

One of the terms that surfaced again and again as the trial was hashed and rehashed is “white privilege.” If you’re not aware of the descriptor, Wikipedia covers it quickly. It’s a relatively new concept that puts white people, privileged people, in the role of “oppressor.” What is dangerous to me about this is that it is, like so many other themes, created to divide rather than blend, hugely divisive. It’s also dismissive of this country’s history. The Great Depression, The Dust Bowl, and so many other periods united Americans in shared suffering and poverty. Don’t get me wrong, all things being equal, I think it’s still far more difficult to be black in America–in the world for that matter– than white, but it’s that divisive them and us that I fight every step of the way. Rush, Al, and Jesse all have become rich by having us tear into each other.

I’ve talked ad nauseum about writing cozy mysteries for Cozy Cat Press and the comfort I felt growing up in a small town. In that town, though, the fifties were like most other towns: racially divided. I was part of that divide as a privileged little white girl. Don’t get too excited, my life took a turn in early high school that veered far from privilege. Anyway, there was a “black” part of town; only in that day it was not referred to as black. And though my classes were racially mixed and kids played together in school, black children and white children parted ways after school. This next part of the story will cast my mother in a not-so-good light but remember this was before Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society and the eloquence and magnificence of Dr. Martin Luther King. Because the Campfire leader had to step down, she asked my mother to take her place. Long story short, I loved that my mother was the new leader and wanted all my friends to be part of the group. One of the friends was a cute, smart little girl named Pat. She was kind, creative, fun–and black. I couldn’t imagine leaving her out. Even though I was only about eight, when I asked my mother if Pat could join, I recognized her reluctance. But I wheedled so she caved. The first few meetings went well, and after each, I walked Pat halfway to where she lived, on the other side of town. But mothers of the other girls started to complain that there was a black girl in the group. And, worse yet according to them, “other black girls want to join.” My mother had a lot of pressure on her so she did something which she later regretted, and which put me in a terrible spot. She told me I would have to tell Pat she couldn’t be part of the group. I was young and sick to my stomach when I told trust little Pat why she could no longer be part of the group. I don’t remember what I told her, but i know it wasn’t the truth. Fast forward sixty years to the obituary of a local man a few weeks ago. He had a last name I would never forget, and In the “surviving him” section was an aunt in North Carolina. I knew immediately it was my Pat, the little girl who had haunted me. After weeks of debating with myself about whether or not I should, I phoned Pat. After a cheery conversation, I apologized for the Campfire Girls incident. I could actually see the smile in her voice when she said, “I don’t remember that, Lyla. I just remember that I stopped going. I want you to know, by the way, that I have had a wonderful life.” She has. She, her children, and husband are success stories. She has traveled widely and far from the small town where we both began. We’ve communicated a couple of times and fully intend to see each other when she comes back to Michigan.

I’ve talked ad nauseum about writing cozy mysteries for Cozy Cat Press and the comfort I felt growing up in a small town. In that town, though, the fifties were like most other towns: racially divided. I was part of that divide as a privileged little white girl. Don’t get too excited, my life took a turn in early high school that veered far from privilege. Anyway, there was a “black” part of town; only in that day it was not referred to as black. And though my classes were racially mixed and kids played together in school, black children and white children parted ways after school. This next part of the story will cast my mother in a not-so-good light but remember this was before Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society and the eloquence and magnificence of Dr. Martin Luther King. Because the Campfire leader had to step down, she asked my mother to take her place. Long story short, I loved that my mother was the new leader and wanted all my friends to be part of the group. One of the friends was a cute, smart little girl named Pat. She was kind, creative, fun–and black. I couldn’t imagine leaving her out. Even though I was only about eight, when I asked my mother if Pat could join, I recognized her reluctance. But I wheedled so she caved. The first few meetings went well, and after each, I walked Pat halfway to where she lived, on the other side of town. But mothers of the other girls started to complain that there was a black girl in the group. And, worse yet according to them, “other black girls want to join.” My mother had a lot of pressure on her so she did something which she later regretted, and which put me in a terrible spot. She told me I would have to tell Pat she couldn’t be part of the group. I was young and sick to my stomach when I told trust little Pat why she could no longer be part of the group. I don’t remember what I told her, but i know it wasn’t the truth. Fast forward sixty years to the obituary of a local man a few weeks ago. He had a last name I would never forget, and In the “surviving him” section was an aunt in North Carolina. I knew immediately it was my Pat, the little girl who had haunted me. After weeks of debating with myself about whether or not I should, I phoned Pat. After a cheery conversation, I apologized for the Campfire Girls incident. I could actually see the smile in her voice when she said, “I don’t remember that, Lyla. I just remember that I stopped going. I want you to know, by the way, that I have had a wonderful life.” She has. She, her children, and husband are success stories. She has traveled widely and far from the small town where we both began. We’ve communicated a couple of times and fully intend to see each other when she comes back to Michigan.

So, like Paula Deen, I have had a racist moment or two in my life. I have since then, however, worked to be fair and nurturing to all people. Teaching made it easy because when you have students you love, and with maybe two horrifying exceptions, I have loved my students, you truly see no color. Because my husband and I made sure that our own two children went to integrated schools, they have a level of comfort with racial difference that helps absolve the guilt I still feel for that heart-piercing incident so many decades ago.

Now I’m a writer. And in publishing there is the whispered theory that white people should not write about people of color, that they somehow lack the understanding or right to tackle the racial divide. This goes against everything I know and believe and also would have eliminated characters like Haper Lee’s Tom Robinson and Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn who taught me more than any textbook about race and its tortured history. One of the reviews of my little mystery Murder on Cinnamon Street said that I had created in a housekeeper named Martha a kind of “Mammy” trope. I winced because in writing about Maurice’s housekeeper, I thought I had created a wise woman whose dialect reflected her lack of education, not intelligence. In the same book, I also put a best friend who is a young black woman with massive intellect and drive. I want my characters of color to be as broad and unique as other characters I create. I seems to me it would be dishonest to do anything else.

Now I’m a writer. And in publishing there is the whispered theory that white people should not write about people of color, that they somehow lack the understanding or right to tackle the racial divide. This goes against everything I know and believe and also would have eliminated characters like Haper Lee’s Tom Robinson and Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn who taught me more than any textbook about race and its tortured history. One of the reviews of my little mystery Murder on Cinnamon Street said that I had created in a housekeeper named Martha a kind of “Mammy” trope. I winced because in writing about Maurice’s housekeeper, I thought I had created a wise woman whose dialect reflected her lack of education, not intelligence. In the same book, I also put a best friend who is a young black woman with massive intellect and drive. I want my characters of color to be as broad and unique as other characters I create. I seems to me it would be dishonest to do anything else.

When I was teaching Wiesel’s Night, years ago, we began to discuss racial hatred and bias, one of my white students said, “Maybe we shouldn’t be discussing this, Mrs. Fox.” What happened this past weekend reaffirmed my feelings that we should be discussing it, but we should play fair. As I told my students that day in class, “This will work if we remember two things: one, that the people in this room didn’t make the problem and two, the problem isn’t over.”